The Material Language of a Singular Artistic Statement

The Foundation of Form and Meaning

Sculptural Materiality is the very bedrock upon which an artistic statement is built, a silent yet profoundly eloquent language that speaks through texture, weight, color, and history. Consequently, to understand a singular artwork is to first understand the conscious choices an artist makes not just in shaping a form, but in selecting the very substance from which that form is born. Therefore, this exploration delves into the intricate dialogue between the creator and their chosen medium, revealing how the physical essence of an object becomes inseparable from its conceptual and emotional resonance. Additionally, we will investigate how this profound connection translates from the gallery to the intimate spaces of our homes, transforming a living area into a stage for a singular, material narrative. Moreover, the inherent properties of any given substance—be it the cold, unyielding nature of granite or the warm, forgiving grain of wood—carry with them millennia of geological, biological, and cultural history. As a result, when an artist engages with a material, they are not merely manipulating inert matter; they are, in fact, entering into a conversation with this deep, embedded history. In this way, the final artwork becomes a testament not only to the artist’s vision but also to the intrinsic story of the material itself. Specifically, this article will unpack the layers of this language, demonstrating how every facet of a material’s being contributes to the power of a singular artistic statement.

The Ancient Language of Stone and Wood

Previously, the foundational vocabulary of three-dimensional art was carved from the earth and the forest, with stone and wood serving as the primary conduits for human expression. For example, ancient civilizations looked to materials like marble, not just for its durability, but for its association with purity, divinity, and permanence. Similarly, the great sculptors of the Renaissance, such as Michelangelo, spoke of releasing a figure from within the stone, suggesting a collaborative process where the material’s potential was as important as the artist’s chisel. Likewise, wood has always communicated a language of life, growth, and connection to the natural world. In addition, its grain tells a story of years and seasons, and its response to the carver’s tools speaks of a yielding, organic partnership. Furthermore, the selection between a dense, dark ebony and a light, porous pine was a critical artistic decision, fundamentally altering the conceptual weight and emotional temperature of the finished piece. Basically, these traditional materials were chosen for their ability to endure, to carry a legacy through time, making them ideal vessels for religious icons, political monuments, and cultural artifacts. Consequently, the tangible essence of these early sculptures is inextricably linked to our collective understanding of history, tradition, and the enduring human spirit.

Industrial Materials and the Modernist Revolution

Afterwards, the dawn of the industrial age introduced a radical new vocabulary into the artist’s lexicon, fundamentally challenging and expanding the possibilities of material expression. Consequently, artists of the early twentieth century began to embrace materials born of industry, such as steel, glass, and concrete, as a way to break from the past and articulate a new, modern reality. For example, the Constructivists utilized iron and glass not for their representative potential, but for their intrinsic qualities of strength, transparency, and engineered precision. In this way, the material itself, in its raw and unadorned state, became the subject of the artwork. Furthermore, this shift represented a move away from carving and modeling towards construction and assembly, a process that mirrored the manufacturing and engineering feats of the era. Similarly, Minimalist artists in the mid-century pushed this idea to its logical conclusion, creating works from industrial plywood, aluminum, and fluorescent light tubes where the “art” was nothing more than the straightforward presentation of the substance. Therefore, the cold, impersonal finish of a steel cube or the stark glow of a neon light was intended to provoke a direct, unmediated experience between the viewer and the object’s physical presence. Actually, this revolution stripped away historical narrative and emotional sentiment, focusing instead on the pure, phenomenal reality of the material in space.

Decoding the Intrinsic Voice of Materials

Specifically, every material possesses an intrinsic voice, a set of inherent characteristics that an artist can either amplify, subvert, or place into dialogue with other elements to construct meaning. First, consider the property of weight and density. Actually, a sculpture by Richard Serra, made from tons of Cor-Ten steel, communicates a sense of immense gravity, danger, and architectural permanence that could never be achieved with a lighter material like aluminum. Conversely, an artist might use a lightweight foam carved to look like stone, creating a deliberate tension between our visual expectation and the object’s physical reality. Second, texture and surface play a crucial role in our psychological and tactile engagement with a work. For example, the rough, aggregate-filled surface of brutalist concrete invites a different kind of contemplation than the flawless, reflective polish of a Jeff Koons balloon dog. In addition, the former speaks of raw process and authenticity, while the latter speaks of perfect, untouchable commodity. Third, color and the potential for patina are fundamental to a material’s narrative arc. Moreover, the vibrant, unyielding color of industrial plastics suggests a sense of permanence and artificiality. Nevertheless, the gradual development of a green patina on bronze or rust on iron tells a story of time, environment, and decay, embedding the artwork within the natural processes of the world. In this way, the surface becomes a living record of its own history.

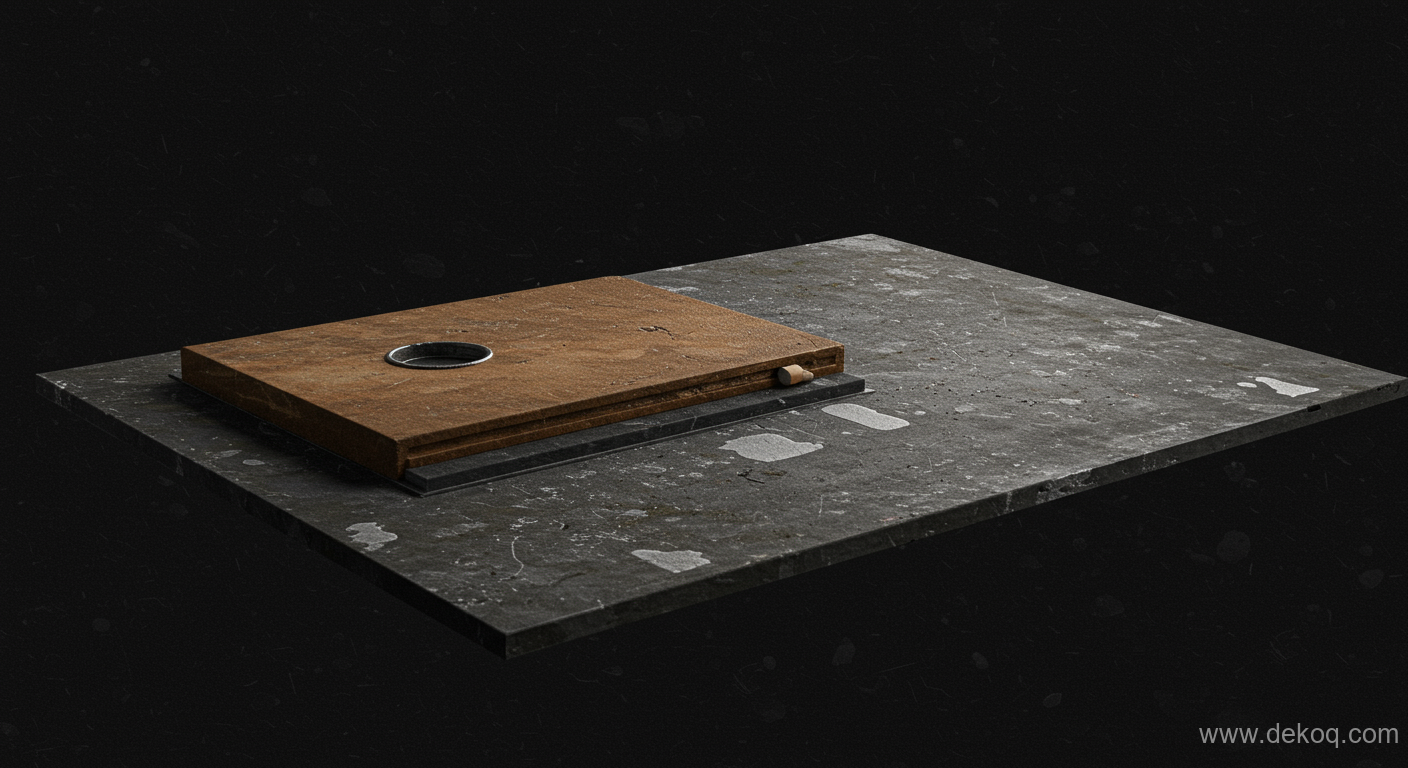

Juxtaposing Substances for Conceptual Depth

Furthermore, one of the most powerful strategies in the material language of art is the juxtaposition of different substances to create conceptual friction and new meaning. In this case, an artist might combine elements with opposing qualities to highlight their individual characteristics and generate a compelling dialogue. For example, placing a fragile, transparent sheet of glass against a rough, opaque block of concrete forces the viewer to contemplate ideas of vulnerability and strength, ephemerality and permanence. Similarly, the work of Arte Povera artists in the 1960s often involved combining “poor,” everyday materials like soil, rags, and twigs with “richer,” more traditional artistic elements, thereby challenging the very definition of what constitutes a worthy artistic medium. Additionally, this act of combination can be deeply symbolic. Actually, an artist might weave discarded electronic wires into a natural fiber tapestry, creating a commentary on the fraught relationship between technology and nature. Also, the fusion of a cold, rigid material like steel with a soft, pliable one like felt can evoke complex human experiences, suggesting both an external armor and an internal vulnerability. As a result, the meaning of the artwork arises not just from the individual materials themselves, but from the energetic space created between them. Therefore, this strategic combination transforms simple objects into a complex and layered artistic statement.

Integrating Material Statements in Interior Design

Moreover, the principles that govern the material language of a singular artwork are profoundly relevant within the realm of interior design, where a single, powerful piece can define and elevate an entire space. Specifically, when selecting an artwork for a home, one must look beyond mere color and shape and consider the physical substance of the piece. Therefore, understanding and Interpreting the Form of a Central Living Room Artwork involves a deep appreciation for its material makeup. For example, a large-scale woven textile sculpture introduces a softness, warmth, and acoustic dampening quality that a polished metal piece cannot. Consequently, it fosters an atmosphere of comfort and intimacy. Conversely, a monolithic sculpture made from a single block of polished stone or a seamless, reflective form can create a powerful focal point, speaking a language of minimalism, strength, and permanence. In addition, this concept of a singular material making a bold statement extends beyond standalone art. Basically, the choice of a feature like a Beyond Grout The Single-Slab Minimalist Backsplash operates on the same principle, where the uninterrupted beauty and character of the stone itself becomes the art. Likewise, the seamless construction of The Reflective Monolith Anatomy of a Seamless Mirrored Wardrobe uses its reflective material to manipulate light and space, turning a functional object into a dynamic sculptural element within the room. Afterwards, homeowners and designers who grasp this material language can curate spaces that are not just decorated, but are conceptually coherent and emotionally resonant. For those seeking further inspiration, you can Search on Google for examples of how artists and designers use these principles. Besides, you can also Watch on YouTube to see visual explorations of these ideas in real-world settings.

Case Studies in Material Expression

Furthermore, examining specific artistic practices can vividly illustrate how a focused material choice becomes a signature language. First, consider an artist who works exclusively with reclaimed timber sourced from dilapidated buildings. Actually, each piece of wood carries a tangible history—old nail holes, weathered paint, and the scars of time become integral parts of the final composition. In this way, the artist is not just creating a new form but is also acting as a custodian of memory, crafting a dialogue between the wood’s past life and its new artistic purpose. Consequently, the material’s history infuses the sculpture with a sense of narrative and soul that a freshly milled piece of lumber could never possess. Second, imagine a sculptor who utilizes polished stainless steel to create large, minimalist forms. In this case, the primary quality of the material is its capacity for reflection. Therefore, the artwork is never static; it is constantly in flux, capturing and distorting its surroundings, the changing light of the day, and the movement of the viewer. As a result, the environment and the observer become active participants in the piece, dissolving the boundary between the object and its context. The material’s language, here, is one of interaction, perception, and the present moment. Third, think of an installation artist who uses ephemeral materials like ice, salt, or unfired clay. Simultaneously, these substances are chosen for their inherent instability and their relationship with time and natural forces. Subsequently, a sculpture carved from ice is destined to melt, its existence a fleeting performance that speaks to themes of impermanence, loss, and cyclical change. Specifically, the artwork’s meaning is deeply embedded in its inevitable transformation and disappearance, a powerful statement that a permanent material like bronze could never make.

The Viewer’s Dialogue with Tangible Art

Ultimately, the material language of a singular artistic statement is only fully realized in its encounter with the viewer. Actually, our engagement with a three-dimensional object is a deeply phenomenological experience, one that involves not just our eyes but our entire bodies and our ingrained understanding of the physical world. For example, when we stand before a massive, rough-hewn stone sculpture, we intuitively feel its weight and permanence, and our bodies respond to its commanding presence in space. Likewise, when confronted with an artwork made of soft, cascading fabric, we might feel a sense of comfort, or our minds might recall the sensation of touch and the yielding nature of the material. Additionally, the surface of a work beckons a tactile response, even if we are forbidden to touch it in a gallery setting. Moreover, our eyes can “feel” the cold smoothness of polished chrome, the coarse texture of raw concrete, or the delicate fragility of glass. In this way, the material speaks directly to our sensory memory. Furthermore, scale plays a critical role in this dialogue. Therefore, an object small enough to be held in one’s hand communicates a sense of intimacy and personal connection, while a monumental work that towers over the viewer evokes feelings of awe, submission, or even intimidation. Consequently, the viewer is not a passive recipient of the artist’s message but an active participant in a silent, physical conversation. Basically, our perception and bodily response complete the circuit, bringing the material’s voice to life.

The Enduring Power of Tangible Artistic Statements

In conclusion, the substance chosen by an artist is never a neutral or passive container for an idea; it is an active and essential agent in the creation of meaning. Although a concept may be the initial spark, it is through the specific qualities of a material—its history, texture, weight, and response to light and time—that the concept achieves its full, resonant voice. Previously, we have seen how traditional materials carry the weight of history, and how modern materials broke with that past to speak of a new age. Afterwards, we explored how the intrinsic properties of matter itself form a rich vocabulary for artists to use. Additionally, the strategic juxtaposition of these substances can create complex conceptual dialogues, a principle that effectively extends into the thoughtful curation of art and design within our personal spaces. Therefore, the profound impact of a singular artistic statement lies in this perfect synthesis of idea and matter, where the form cannot be mentally separated from the physical stuff of its being. In this way, the material language of art reminds us of the power of the tangible world in an increasingly digital age. Finally, it affirms that the most enduring messages are often those we can not only see, but can also, on a deeper level, feel.